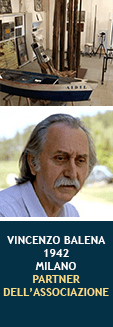

Casa Partner dell'Associazione

Vincenzo Balena (born in Milan, in 1942) began his career as an artist in the 1960s when the movement known as Existential Realism was in vogue, and initially devoted his attention to the study of animal morphology. From the early 1970s he exhibited regularly at the Montrasio Gallery in Monza and at the Naviglio Gallery in Milan. His work soon attracted the attention of art historians and critics such as Mario De Micheli and Marco Rosci, and later by Rossana Bossaglia, Carlo Pirovano and Lea Vergine. In the early 1980s, when he was influenced by the work of Pier Paolo Pasolini (to whom he dedicated a series of paintings and sculptures), Balena came into contact with such poets and writers as Antonio Porta, Giovanni Raboni and Roberto Sanesi, and with many other writers and art critics in the years that followed. Raboni in particular examined in some depth his later work on the human body: the so-called Disiecta Membra, consisting of body parts fashioned in clay and suspended on wires. This was followed by sculptures in wax, bronze, wood and embossed aluminium, and exhibitions in major venues in Italy (the House of Giorgione in Castelfranco Veneto) and abroad (Düsseldorf, Prague and New York). Balena also worked intensively in the theatre. He produced sculptures and masks for the stage, including for the 1989 play entitled Nel tempo che non è più e non è ancora (“In Times Gone By And Times Still To Come”) at the Teatro del Buratto, with texts by Maurizio Cucchi, the poet who presented him many years later at the 54th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale. Masks have been something of a constant in the work of Balena, and were also the focus of a memorable 2014 exhibition at Villa Badoer in Fratta Polesine (near Rovigo), where a cycle of works dating back to 2005 and 2006 (Antiqua Terra Mater) were set against the backdrop of the grottesche decorations inside the Palladian villa.

His more recent work, with its explicit figurative references, explores the as yet untapped expressive resources to be found in the rejection of technology: that artificial extension of the human mind rescued from an electronics-engendered oblivion. The 2017 exhibition at the Lorenzo Vatalaro Gallery in Milan marks a new turning point in his work, much of which nonetheless is still very true to itself. The artist has painstakingly retrieved manipulated circuits from the earliest computers, generating pages of shorthand and mysterious archaic scriptures, which are presented in a way that elegantly (but slightly disconcertingly) hints at primordial chaos, at obscure origins – and to which the use of backlighting gives a particularly hypnotic power.